SA's 'Test' Case of Expropriation Without Compensation

Multimillion-rand development property expropriated without compensation in Gauteng, South Africa.

South Africa’s first case of expropriation without compensation for a government housing project is heading to court.

The ANC-controlled City of Ekurhuleni (eastern Johannesburg) in Gauteng province has expropriated a 34-hectare property called portion 406 of the Farm Driefontein without compensation to “test the limits of Section 25 of the Constitution”.

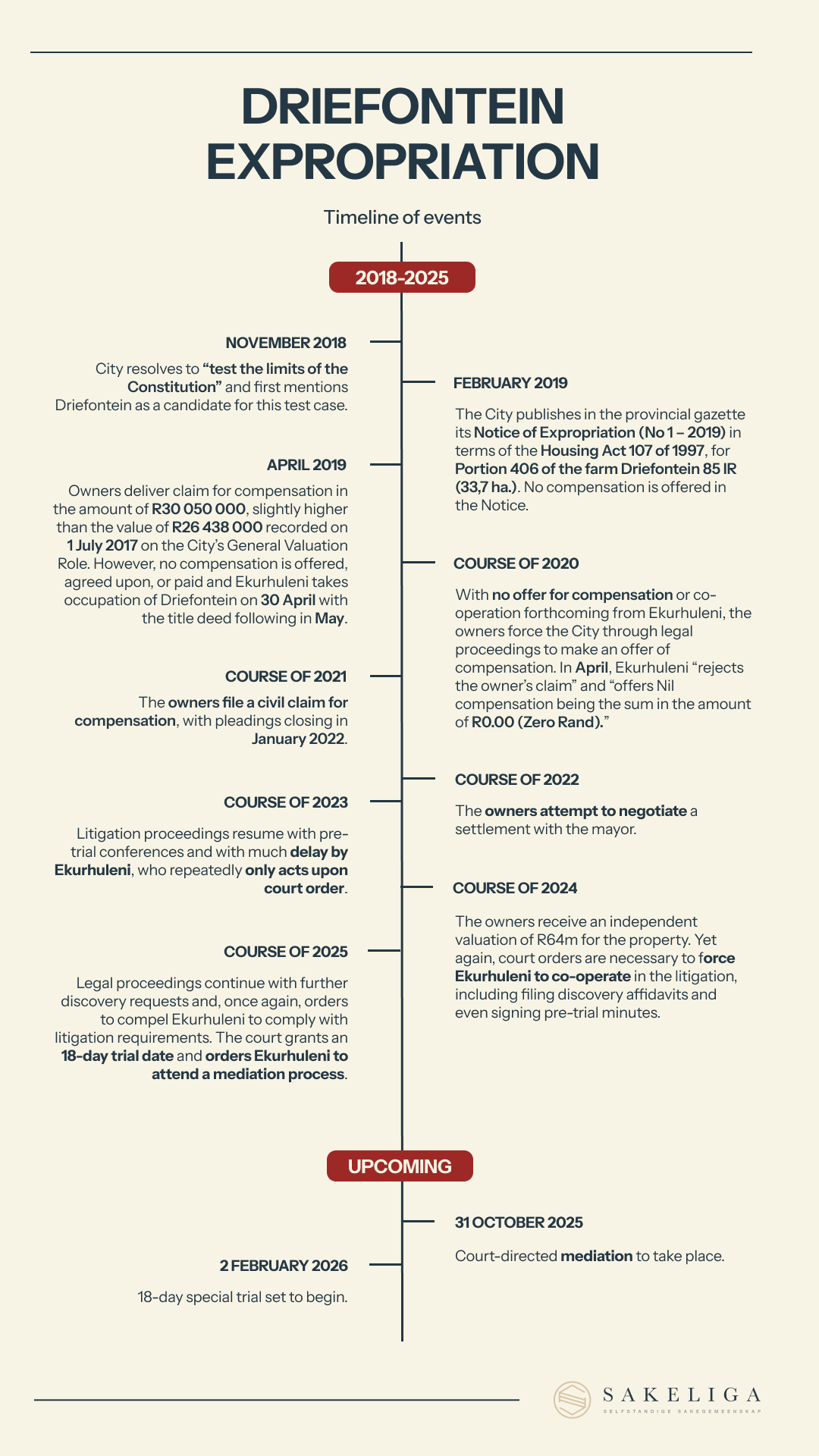

Six years after the initial notice of expropriation in February 2019 the matter is now scheduled for court-directed mediation in October and an 18-day trial in February 2026, because the city government refuses to pay any compensation. At the time of expropriation, the owner was applying for development rights and the property was valued at no less than R30m, with independent valuations since then ranging as high as R64m.

If market-related compensation is not restored, the case will herald an economic, political, and social crisis in South Africa.

Since losing possession of its property in 2019, the former owner, Business Venture Investments 900, had gone to extraordinary lengths to avoid public controversy and to seek an amicable resolution to overturn the “offer” of nil compensation.

However, with all other avenues exhausted and millions already spent in legal fees, lost development opportunity, and management time, it is now preparing for trial.

In addition to the owner’s independent and ongoing attempt at recourse, Sakeliga is taking legal, political, diplomatic, and business-coordination measures directed at rectifying and preventing expropriation without compensation.

Demonstration of government intent

The case demonstrates what the ANC and other advocates of the new Expropriation Act of 2024 intend to achieve: extensive expropriation without compensation of both agricultural and urban land, through reliance on a combination of arbitrary decisions and lawfare, couched in public interest language.

The state’s emerging modus operandi can be broadly summarised as follows:

● First, a state entity identifies land the expropriation of which could somehow be claimed as being “in the public interest” (e.g. for housing projects or land redistribution).

● Based on this alleged “public interest” the state entity then denies that any compensation is payable and unilaterally takes possession of the properties.

● With ownership transferred, the state entity then refuses to further engage the former owners, on whom now rests the onus to challenge the compensation decision with years of litigation, millions in legal fees, and unwanted public exposure.

In the Driefontein case, the City took the position that it “believes its offer of Nil compensation is just and equitable and was arrived at after having shown that the equitable balance favours the interest of the public.” Based on a “substantive consideration of social justice and the lived experiences of those who are landless and subjected to inhuman living conditions in informal settlements,” it concluded that market value has no bearing on the matter. It even alleged that the owner suffered “no financial loss as a result of the expropriation” and that because the land was supposedly held for speculative purposes it did not qualify for compensation.

Since the test case was conceived when the Expropriation Act of 1975 was still in effect, the owner invoked its provisions in an attempt to secure compensation. However, in a telling response to the owner’s claim for compensation, the City filed a counterclaim, seeking an order that the 1975 Act is unconstitutional and that Section 25 of the Constitution of South Africa allows for expropriation without compensation.

Notably, the Driefontein expropriation enjoys the public backing of high-ranking ANC members. The former executive mayor of Ekurhuleni, Mzwandile Masina, who originally and proudly announced this episode as a “test case,” currently serves as a member of the ANC’s National Executive Council. He has acted as spokesman for the party on expropriation several times in 2025 already, and is the chairman of the Portfolio Committee on Trade, Industry and Competition in the National Assembly.

Measures by Sakeliga

Measures undertaken and envisaged by Sakeliga to rectify the matter include the following:

- Our legal team is monitoring the matter and taking it into account for our and our partners’ upcoming litigation on the Expropriation Act 13 of 2024, to be filed later this year. The Driefontein case illustrates starkly the shortcomings of the Expropriation Act of 2024 compared to its predecessor from 1975.

- We have invited the DA, FF+, and IFP to participate in discussions on appropriate political measures, as parties in the current governing coalition that voted against the Expropriation Act last year.

- We have alerted trade representatives of foreign missions in South Africa. This includes among others trade representatives of the United States, in light of the objection to expropriation without compensation raised in the 7 February 2025 Executive Order on “Addressing Egregious Actions of The Republic of South Africa”.

- We are monitoring other cases of expropriation and will be alerting property development companies and related businesses, as well as business representative organisations in our network, with a view to co-ordinated protective measures.

Some consequences if the expropriation without compensation is not reversed

If the Driefontein expropriation without compensation is left to stand, it would have far-reaching consequences.

Economically, valuations for all similar properties would have to be adjusted downward, constituting a loss to all direct and indirect, local and international holders of interest in such properties. As loan-to-value ratios of collateralised property decline, ripple-effects will be felt throughout financial markets. Uncertainty of property ownership has wide-ranging and deeply harmful effects on land stewardship, development, and trade, with knock-on harms to all productive economic and social land use.

Politically, one should expect severe strain on the current coalition government and also within political parties in the coalition or aspiring to be in future local and national coalitions. Moreover, foreign political scrutiny will escalate sharply, causing a crisis of legitimacy in the international arena.

And socially, allowing this expropriation without compensation to stand would quickly invite other state entities in South Africa to attempt the same and worse, and would embolden the organisers of illegal land invasions to unprecedented degrees.

Origins of the Driefontein expropriation

The origins of the Driefontein matter go back to September 2018, when the Ekurhuleni City Council resolved to “test the limits of Section 25 of the Constitution in order to accelerate inclusive social housing development.” The City proceeded to expropriate Driefontein in the first quarter of 2019 and only in April 2020 finally ventured to make the owner an “offer”, albeit for zero (nil) compensation, followed by what has now become years of delays.

Contrary to averments by the City, the owner was developing the property and had already in August 2018 obtained approval from Ekurhuleni for township establishment, which was then not proclaimed by the City because of appeals filed against the establishment. The owner’s township application has since been overtaken by the expropriation and they could not continue with it after their property was expropriated in 2019.

Telling conduct by Ekurhuleni and extreme detriment to owners

The approach by the City of Ekurhuleni is illustrative of the extreme detriment to property owners when trying to oppose expropriation without compensation. Even if the owner of Driefontein prevails in court next year or settles in mediation, fending off an attempt by the state to expropriate without compensation is extraordinarily expensive. Costs include legal fees, management time, uncertainty, loss of assets without compensation for years, the risk of public and political controversy, and now court-directed mediation and a trial set down for 18 days.

The City of Ekurhuleni – in keeping with the general approach by state entities in South Africa – appears to feel no shame nor sense of injustice for dragging the expropriated party through legal proceedings for years on end, and remains unperturbed despite three cost orders so far against them.

Resources

Read the court documents here.